Kaspa Network: My technical insights on the Kaspa White paper

Today, let’s talk about Kaspa’s white paper. I want to share my thoughts and understanding from a technical perspective. We’ll focus solely on the protocol’s implementation, without discussing the currency’s value and other unrelated matters.

Table of Contents

Launched a few years ago, Kaspa can be seen as a blockchain that extends Bitcoin’s longest chain consensus mechanism and allows multiple blocks to be created and incorporated in parallel. These blocks and their transactions are then ordered through consensus among nodes to ensure the consistency and security of Kaspa. This is achieved through the “GhostDAG” protocol, which was invented as a scaling solution for Bitcoin. GhostDAG leverages many of Bitcoin’s mechanisms, including Proof-of-Work, but links blocks in a different way.

Question: How does a miner select an existing chain as the previous Proof-of-Work when multiple blocks can be mined simultaneously? Which blocks should the selected chain contain? Are those chains sharing blocks?

Understanding Kaspa’s BlockDAG

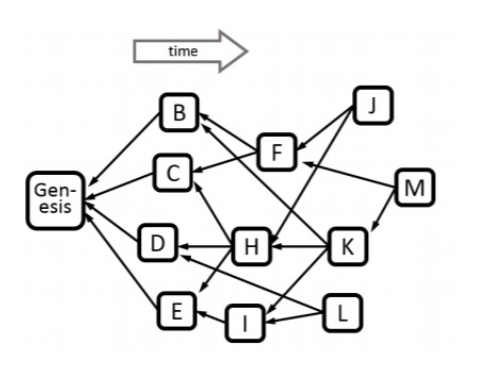

Let’s address this major question. In Bitcoin, the longest-chain consensus requires each block to have a single predecessor, forming a linear chain. In contrast, Kaspa expands this concept into a BlockDAG, a directed acyclic graph of interconnected blocks. Blocks are linked by directed arrows pointing from recent blocks back to the genesis block. The block header contains multiple references to its direct predecessors, represented as a list of hashes. To determine a newly mined block at the tip of the BlockDAG (let’s say block M shown in the graph), the system must ensure that the BlockDAG (in the direction from M to the genesis block) remains valid, secure, and accurate.

GhostDAG Protocol

Blue and Red Blocks

For context, the GhostDAG protocol defines two types of block sets: blue and red. The blue set includes blocks mined by cooperating nodes, forming the main DAG with the highest cumulative weight of connected blocks. In contrast, red blocks are considered to be mined by suspicious or malicious nodes. For a BlockDAG to be a valid reference for previous blocks in mining, it must predominantly consist of blue blocks or the main chain. The BlockDAG we want to find is the Kaspa main chain. There is only one global blue set representing the main chain at any given time. However, but mining nodes may have different views of this set due to factors.

Question: how does a mining node determine the main chain then?

Greedy Algorithm

The goal of the GhostDAG protocol is to identify the main chain as the maximum k-cluster SubDAG within the entire Kaspa network, viewed as a large DAG. While finding the largest SubDAG across the whole network is challenging in practice, the GhostDAG algorithm employs a Greedy approach to select the largest cluster of blue blocks it can find, starting from the currently mined block, thereby qualifying as the BlockDAG for mining.

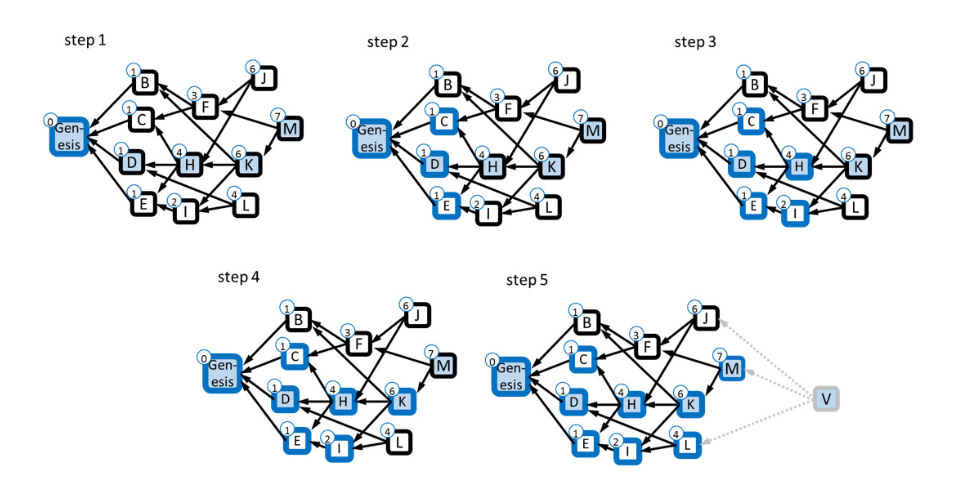

Let’s talk about the GhostDAG Greedy algorithm in more detail.

Consider block M as the block being mined. The process begins by finding a suitable path from M to the genesis block by evaluating the score of each predecessor block. The block score is determined by the number of its predecessors. The path is M - K - H - D - Genesis. Then, the blue block set is created recursively along the path, starting from the genesis block and adding its predecessors to the blue set. Note that a predecessor block is not added to the set if its anticone (the set of blocks outside the current block’s reach) contains too many other blue blocks. This reduces the chance of adding potential red blocks to the main chain. This results in the main chain from the current miner’s perspective that includes Genesis, C, D, E, H, I, K, and M (though some perspectives may vary slightly). For example, if J wants to mine a block, it will find its version of the main chain.

The Greedy algorithm establishes an order for previous blocks and their transactions, helping all miners find the same main chain (though it may vary slightly). This total ordering rule serves as a reference for all miners. Each miner uses this rule to process transactions in their mining block, discarding any conflicting transactions. By following this rule, consistency is ensured among all newly mined blocks operating in parallel, preventing any new blocks from containing conflicting transactions.

Security Considerations

Let’s briefly discuss the security of the Proof-of-Work consensus mechanism with BlockDAG. The ordering rule derived from the heaviest subDAG (main chain) makes it difficult for attackers to insert malicious transactions and cause double-spending. Even large-scale attacks, such as a 51% attack, are mitigated because the malicious chain must be both longer and heavier in cumulative proof-of-work than the legitimate main chain.

The entire GhostDAG protocol is designed to encourage the expansion of the blue set and restrict the red set. For instance, mining incentives motivate participants to create blocks that can be included in the blue set, thereby earning rewards and transaction fees. While red blocks can still be mined and integrated into the network, they are not part of the main chain and will receive only limited rewards.

Unresolved Questions

There are still some unresolved questions I need to explore, such as:

- How does the main chain design impact the decentralization of the Kaspa network? Could it cause an imbalance between the number of red and blue blocks?

- How can Kaspa tokens maintain stability for future micro-payment use cases if mining power becomes centralized?

- What are the resource consumption implications of Kaspa on a large scale?

We will continue the conversation about Kaspa soon.